The Bellamys

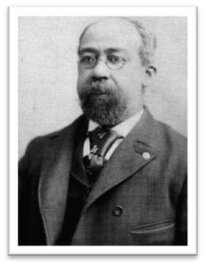

John D. (1817-1896) and Eliza (1821-1907)

John D. (1817-1896) and Eliza (1821-1907)

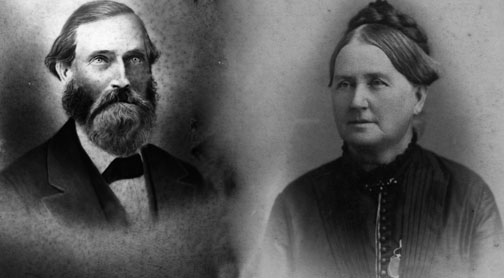

John Dillard Bellamy, M.D. married Eliza McIlhenny Harriss in Wilmington on June 12, 1839. Over the next twenty-two years Dr. and Mrs. Bellamy welcomed ten children to their family as John evolved from a town physician to a successful merchant, prominent planter, and one of the largest slaveholders in the state of North Carolina.

As a young man, John Dillard Bellamy (1817-1896) inherited a large piece of his father’s South Carolina plantation along with several dozen slaves. He soon moved from Horry County, South Carolina, to Wilmington, North Carolina, and studied medicine under Dr. William Harriss before leaving for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1837, to earn his official medical degree. Upon his return to Wilmington, John married Dr. Harriss's eldest daughter, Eliza. By 1860, Dr. Bellamy considered himself a merchant and was involved in everything from founding banks to investing heavily in the railroad industry. He was also engaged in enterprises outside New Hanover County. He owned a large produce plantation in Brunswick County, known as "Grovely," as well as a tar and turpentine operation in Columbus County known as "Grist." According to John D. Bellamy Jr., "Grist" was the most lucrative of Dr. Bellamy's investments.

The myriad business ventures required a vast number of workers---enslaved workers in this case---and by 1860 Dr. Bellamy owned 115 enslaved men, women, and children in three North Carolina counties. At "Grovely," 82 enslaved workers lived and toiled raising livestock and foodstuffs. At "Grist" John kept 26 enslaved men between the ages of 18 and 40 as the tar and turpentine industry involved back-breaking work. At their Wilmington townhome, the Bellamys kept approximately nine domestic enslaved workers on a permanent basis.

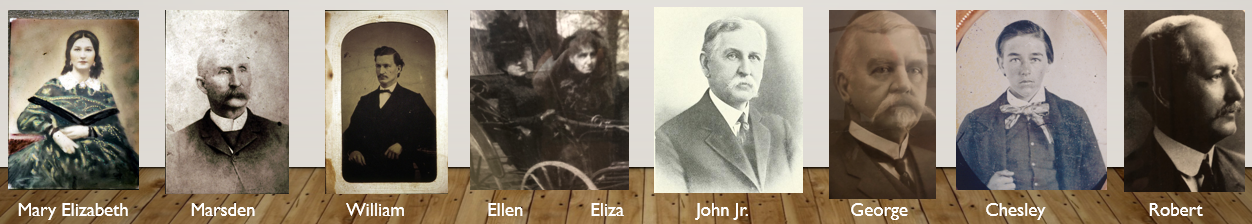

By the time the Bellamy family moved into their new home at 503 Market Street in early 1861, the family included eight children who ranged in age from nineteen-year-old Mary Elizabeth to 18-month-old Chesley. One Bellamy, Robert, was born in the mansion in the summer of 1861. Click here to learn more about the Bellamy family.

As a young man, John Dillard Bellamy (1817-1896) inherited a large piece of his father’s South Carolina plantation along with several dozen slaves. He soon moved from Horry County, South Carolina, to Wilmington, North Carolina, and studied medicine under Dr. William Harriss before leaving for Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1837, to earn his official medical degree. Upon his return to Wilmington, John married Dr. Harriss's eldest daughter, Eliza. By 1860, Dr. Bellamy considered himself a merchant and was involved in everything from founding banks to investing heavily in the railroad industry. He was also engaged in enterprises outside New Hanover County. He owned a large produce plantation in Brunswick County, known as "Grovely," as well as a tar and turpentine operation in Columbus County known as "Grist." According to John D. Bellamy Jr., "Grist" was the most lucrative of Dr. Bellamy's investments.

The myriad business ventures required a vast number of workers---enslaved workers in this case---and by 1860 Dr. Bellamy owned 115 enslaved men, women, and children in three North Carolina counties. At "Grovely," 82 enslaved workers lived and toiled raising livestock and foodstuffs. At "Grist" John kept 26 enslaved men between the ages of 18 and 40 as the tar and turpentine industry involved back-breaking work. At their Wilmington townhome, the Bellamys kept approximately nine domestic enslaved workers on a permanent basis.

By the time the Bellamy family moved into their new home at 503 Market Street in early 1861, the family included eight children who ranged in age from nineteen-year-old Mary Elizabeth to 18-month-old Chesley. One Bellamy, Robert, was born in the mansion in the summer of 1861. Click here to learn more about the Bellamy family.

All of the Bellamy sons were successful and by 1890 included two attorneys (Marsden and John Jr.), a pharmacist (Robert), a farmer/politician (George), and one medical doctor (William). John Jr. served in the North Carolina General Assembly and was eventually elected to the US Congress during the infamous 1898 state elections. Mary Elizabeth was the only Bellamy daughter to marry and have children. Eliza and Ellen both lived out their unmarried days in the family's mansion on Market Street. Ellen passed away in 1946 just shy of her 94th birthday, and no other Bellamy occupied the mansion again.

The Builders

Rufus Bunnell (1835-1909)

Rufus Bunnell (1835-1909)

Dr. John D. Bellamy hired Northern-born architects to design his Wilmington townhome while he contracted enslaved craftsmen and hired free black artisans to execute those plans. Between late 1859 and early 1861, dozens of carpenters, masons, porters, plasterers, and other contracted workers built first the brick slave quarters and carriage house, followed by the 10,000-square-foot mansion.

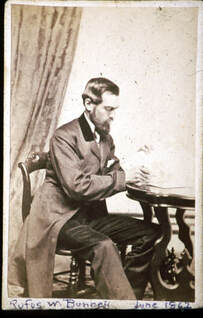

James F. Post, a New Jersey native, was a prolific architect in and around Wilmington who designed many iconic buildings that survive in the downtown area including City Hall-Thalian Hall. No records survive detailing the formal arrangements made between Bellamy and Post, but the project, coupled with Post's burgeoning career in Wilmington, led him to hire an assistant architect in the spring of 1859. Post hired Rufus Bunnell who moved from his native Connecticut to Wilmington to serve as Post's assistant and draftsman. Bunnell kept a diary during his time in Wilmington, and much of what is known about the construction process and workers comes from his writings. An oft asked question that remains a mystery is how much the project cost in total. Receipts in Post's ledger do indicate Dr. Bellamy did not finish paying for the construction until after the Civil War ended in 1865.

James F. Post, a New Jersey native, was a prolific architect in and around Wilmington who designed many iconic buildings that survive in the downtown area including City Hall-Thalian Hall. No records survive detailing the formal arrangements made between Bellamy and Post, but the project, coupled with Post's burgeoning career in Wilmington, led him to hire an assistant architect in the spring of 1859. Post hired Rufus Bunnell who moved from his native Connecticut to Wilmington to serve as Post's assistant and draftsman. Bunnell kept a diary during his time in Wilmington, and much of what is known about the construction process and workers comes from his writings. An oft asked question that remains a mystery is how much the project cost in total. Receipts in Post's ledger do indicate Dr. Bellamy did not finish paying for the construction until after the Civil War ended in 1865.

Frederick Sadgwar (1843-1925)

Frederick Sadgwar (1843-1925)

In his memoirs, John D. Bellamy Jr. recalled, “Even the delicate and ornamental cornice work of plaster of Paris in the rooms was done by Negro mechanics.” He recalled the surnames of some artisans: “Howes, Artises, Prices, Sadgwars, and Kelloggs were also employed in the work.”

Elvin Artis, a free black house carpenter, served as the carpentry foreman. His family traced their free status to the colonial period, and some of his ancestors served in the Revolutionary War. Rufus Bunnell wrote in his diary about Elvin saying, “...strange to ever keep in mind, that almost to a man these mechanics (however seemingly intelligent,) were nothing but slaves and capable as they might be, all the earnings that came from their work, was regularly paid over to their masters or mistresses. A very few, as for instance, the mulatto 'Artis' on the Bellamy house construction, were freedmen made thus by will or purchased freedom; but even those were restricted by special laws made for freed negroes and were also subject if deemed necessary, to observation by the day and night patrol.” The city contracted Elvin for various projects throughout the 19th-century, and he also ran a prominent Wilmington barber shop and hair salon off and on during the 1860s, '70s, and '80s.

Members of Wilmington's prominent Sadgwar family also purportedly helped construct the Bellamy site. David Sadgwar was an enslaved carpenter who, by 1870, had one grown son who was also listed on the census as a "house carpenter" while his three other sons were all "apprenticed to carpenter[s]." His eldest son, Frederick, most likely worked with him on the Bellamy project.

Elvin Artis, a free black house carpenter, served as the carpentry foreman. His family traced their free status to the colonial period, and some of his ancestors served in the Revolutionary War. Rufus Bunnell wrote in his diary about Elvin saying, “...strange to ever keep in mind, that almost to a man these mechanics (however seemingly intelligent,) were nothing but slaves and capable as they might be, all the earnings that came from their work, was regularly paid over to their masters or mistresses. A very few, as for instance, the mulatto 'Artis' on the Bellamy house construction, were freedmen made thus by will or purchased freedom; but even those were restricted by special laws made for freed negroes and were also subject if deemed necessary, to observation by the day and night patrol.” The city contracted Elvin for various projects throughout the 19th-century, and he also ran a prominent Wilmington barber shop and hair salon off and on during the 1860s, '70s, and '80s.

Members of Wilmington's prominent Sadgwar family also purportedly helped construct the Bellamy site. David Sadgwar was an enslaved carpenter who, by 1870, had one grown son who was also listed on the census as a "house carpenter" while his three other sons were all "apprenticed to carpenter[s]." His eldest son, Frederick, most likely worked with him on the Bellamy project.

Henry Taylor (1823-1891)

Henry Taylor (1823-1891)

Another carpenter on the Bellamy project was Henry Taylor. Booker T. Washington described Taylor as, "the son of a white man who was at the same time his master. Although he was nominally a slave, he was early given liberty to do about as he pleased.” Taylor was a successful carpenter-builder and businessman both prior to the end of the Civil War and after. After emancipation, Taylor ran a grocery store as well as continuing with carpentry. His later projects included the Hemenway School and the first black Masonic lodge in Wilmington--Giblem Masonic Lodge. He was also a founding member of the Chestnut Street Presbyterian Church and active in local politics.

Taylor and his wife, Emily Still Taylor, raised four children in Wilmington. Their son, Robert R. Taylor, was the first black graduate of M.I.T. and the first accredited black architect in the United States. Other descendants include Howard University graduates and his great-great granddaughter, Valerie Jarrett, served as senior advisor to President Barack Obama.

Taylor and his wife, Emily Still Taylor, raised four children in Wilmington. Their son, Robert R. Taylor, was the first black graduate of M.I.T. and the first accredited black architect in the United States. Other descendants include Howard University graduates and his great-great granddaughter, Valerie Jarrett, served as senior advisor to President Barack Obama.

WB Gould I (1837-1923)

WB Gould I (1837-1923)

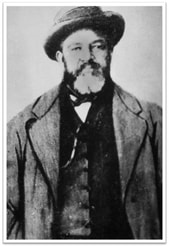

William B. Gould I was yet another enslaved artisan hired for the Bellamy project. Gould was a master plasterer who likely worked on many Wilmington homes, though the Bellamy mansion is the only known project attributed to him. William, along with several other slaves, escaped to their freedom in 1862 by boat down the Cape Fear River. The "contraband" were picked up by the Union Navy, and Gould served the remainder of the Civil War in the Union Navy on several ships.

Gould began keeping a diary just days after his escape, and he kept it for three years. After the War, Gould and his wife, Cornelia Read Gould, settled in Massachusetts and raised eight children. Their descendants include William B. Gould IV, an American lawyer who was the first black professor at Stanford Law School. Gould IV is currently the Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law, Emeritus at Stanford Law School who served as the Chairman of the National Labor Relations Board from 1994 to 1998. Gould IV published his great-grandfather's memoirs entitled Diary of a Contraband.

Gould began keeping a diary just days after his escape, and he kept it for three years. After the War, Gould and his wife, Cornelia Read Gould, settled in Massachusetts and raised eight children. Their descendants include William B. Gould IV, an American lawyer who was the first black professor at Stanford Law School. Gould IV is currently the Charles A. Beardsley Professor of Law, Emeritus at Stanford Law School who served as the Chairman of the National Labor Relations Board from 1994 to 1998. Gould IV published his great-grandfather's memoirs entitled Diary of a Contraband.

The Enslaved Domestic Workers of the Bellamy Site

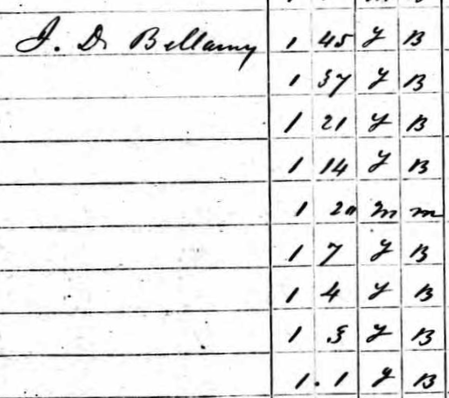

Dr. John D. Bellamy kept approximately nine of his 115 enslaved workers at his Wilmington town home on a permanent basis. The 1860 county slave census detailed the enslaved person's age, sex, and if they were "black" or "mulatto" beside the name

of their owner. Dr. Bellamy's household, 1860 census shown at left, included (in census order):

Sarah--cook and housekeeper

Rosella Bellamy Simmons--laundress

Joan--wet nurse and nanny

Mary Ann Nixon--housekeeper

Guy Nixon--butler and coachman

Caroline--Joan's daughter and Mrs. Bellamy's "maid"

Harriett Potter Hill--Rosella's daughter

Charlotte Potter--Rosella's daughter

Unnamed 1-year old girl

of their owner. Dr. Bellamy's household, 1860 census shown at left, included (in census order):

Sarah--cook and housekeeper

Rosella Bellamy Simmons--laundress

Joan--wet nurse and nanny

Mary Ann Nixon--housekeeper

Guy Nixon--butler and coachman

Caroline--Joan's daughter and Mrs. Bellamy's "maid"

Harriett Potter Hill--Rosella's daughter

Charlotte Potter--Rosella's daughter

Unnamed 1-year old girl

Most of what was known about these individuals for decades came from Back With the Tide, the memoirs of Ellen Douglas Bellamy. From names to job descriptions, Ellen provided scant information for some of the workers, but many details including surnames and familial connections were not uncovered until recently. Dedicated research by Bellamy staff, much of it made possible by the Women's Impact Network of New Hanover County, has revealed new information detailed in a brochure available at the museum. Download a Word version of the brochure by clicking here.