The Main House

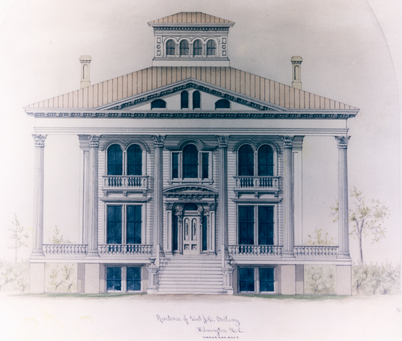

Elevation drawn by Rufus Bunnell, assistant architect.

Elevation drawn by Rufus Bunnell, assistant architect.

Designed by architect James F. Post for the wealthy physician and merchant Dr. John D. Bellamy, the 10,000-square-foot, twenty-two room mansion was constructed primarily by skilled, enslaved workers and local, free black artisans between 1859 and 1861.

The mansion does not boast a pure architectural style, but shares elements of Greek Revival and Italianate styles. Twenty-five foot tall Corinthian columns bring an onlooker’s eye up to the ornate wood trimwork that includes dentil molding and an egg and dart motif. Every aspect of the mansion’s design was deliberate. From placing the kitchen on the east side of the home so it received the first light of day to placing a belvedere at the very top that acted as a sort of early air conditioning, James F. Post and his assistant architect Rufus Bunnell left nothing to chance.

Today, guests can explore the mansion from basement to belvedere as the entire mansion is accessible on self-guided and guided tours of the site. Touring the mansion does require climbing multiple flights of stairs and is not handicapped accessible. The museum does offer a 30-minute video tour of the mansion for those with limited mobility. The mansion and carriage house visitor center are both air-conditioned.

The mansion does not boast a pure architectural style, but shares elements of Greek Revival and Italianate styles. Twenty-five foot tall Corinthian columns bring an onlooker’s eye up to the ornate wood trimwork that includes dentil molding and an egg and dart motif. Every aspect of the mansion’s design was deliberate. From placing the kitchen on the east side of the home so it received the first light of day to placing a belvedere at the very top that acted as a sort of early air conditioning, James F. Post and his assistant architect Rufus Bunnell left nothing to chance.

Today, guests can explore the mansion from basement to belvedere as the entire mansion is accessible on self-guided and guided tours of the site. Touring the mansion does require climbing multiple flights of stairs and is not handicapped accessible. The museum does offer a 30-minute video tour of the mansion for those with limited mobility. The mansion and carriage house visitor center are both air-conditioned.

The Slave Quarters

Restoration of the entire building was completed in 2014.

Restoration of the entire building was completed in 2014.

On the northeast corner of the lot stands the original two-story brick slave quarters. The neatly but plainly finished brick building typifies urban slave quarters in the late antebellum South—one room deep and three rooms wide, with stepped parapets rising above the roof and a windowless back wall along the property line. While now rare, this type of slave quarters could once be found in any city where slavery was legal—from New York to New Orleans—and stands in stark contrast to the small, crude slave huts associated with plantations and rural areas.

James F. Post designed both the exteriors of the slave quarters and the carriage house to complement the main house. From the lime washed brick walls to the matching window styles, the three buildings share many aesthetic features. The slave quarters building includes four sleeping chambers, a laundry room, and two five-seat privies.

Today, visitors can tour through both levels of the original slave quarters—one of the best-preserved examples in the country. One sleeping chamber, the laundry room and privies can all be toured without climbing stairs. Three sleeping chambers are located on the second floor and require climbing one fairly steep set of stairs to access. The building is not air-conditioned.

James F. Post designed both the exteriors of the slave quarters and the carriage house to complement the main house. From the lime washed brick walls to the matching window styles, the three buildings share many aesthetic features. The slave quarters building includes four sleeping chambers, a laundry room, and two five-seat privies.

Today, visitors can tour through both levels of the original slave quarters—one of the best-preserved examples in the country. One sleeping chamber, the laundry room and privies can all be toured without climbing stairs. Three sleeping chambers are located on the second floor and require climbing one fairly steep set of stairs to access. The building is not air-conditioned.

The Gardens

1995 photograph of a bare formal garden.

1995 photograph of a bare formal garden.

Eliza Harriss Bellamy, wife of Dr. John D. Bellamy, began planning and planting her formal garden sometime after the end of the Civil War. Family tradition says Mrs. Bellamy’s even kept a botanical notebook, but unfortunately, the notebook’s location remains a mystery.

The original formal garden plans included a series of elliptical and circular parterre beds whose crushed shell paths acted as a sort of drainage system. The most successful plantings were hardy native species that could withstand the extended hot summers, but the garden boasted color throughout the entire year. After Mrs. Bellamy’s death in 1907, the formal garden began a slow decline.

By the late 1940s the formal garden was completely overgrown, and by the time the mansion restoration began in 1992, virtually all traces of the original had disappeared. The gardens were fully restored in 1996.

The original formal garden plans included a series of elliptical and circular parterre beds whose crushed shell paths acted as a sort of drainage system. The most successful plantings were hardy native species that could withstand the extended hot summers, but the garden boasted color throughout the entire year. After Mrs. Bellamy’s death in 1907, the formal garden began a slow decline.

By the late 1940s the formal garden was completely overgrown, and by the time the mansion restoration began in 1992, virtually all traces of the original had disappeared. The gardens were fully restored in 1996.

2003 photograph of the restored formal garden.

2003 photograph of the restored formal garden.

Most of what is known about the formal garden's design is the product of a two-year investigation. The archaeological excavations, coordinated by the University of North Carolina Wilmington (UNCW), revealed the configuration of the beds and the materials of the paths—oyster, clam, and scallop shells.

Historic photographs and personal recollections described specific plant choices and locations. One of the most striking features are the four original magnolia grandifloras that tower over visitors as they wander the shell paths today.

Unlike the formal garden, the lot’s rear yard was a working area more akin to a barnyard. The carriage house, slave quarters and poultry shed supported the endless tasks of enslaved workers and later servants. The rear yard housed a kitchen garden with herbs and other edible flora along with medicinal plants. UNCW conducted a full-scale archeological investigation of the rear yard between 1997 and 1999.

Historic photographs and personal recollections described specific plant choices and locations. One of the most striking features are the four original magnolia grandifloras that tower over visitors as they wander the shell paths today.

Unlike the formal garden, the lot’s rear yard was a working area more akin to a barnyard. The carriage house, slave quarters and poultry shed supported the endless tasks of enslaved workers and later servants. The rear yard housed a kitchen garden with herbs and other edible flora along with medicinal plants. UNCW conducted a full-scale archeological investigation of the rear yard between 1997 and 1999.