|

Following in the tradition of the original enslaved plasterers, William M. Hill, a second-generation master plasterer from Clinton, NC, and his team of artisans repaired extensive plaster damage resulting from the 1972 fire at the Bellamy Mansion. During 1992 and 1993 — 20 years after the blaze set by arsonists — they restored the ornamental plasterwork and fabricated the missing parts by hand. Hill's journey to become a master of his craft was a fascinating one, as uncovered by historian David Cecelski in a 2006 interview with Hill, then age 77, published in The Raleigh News & Observer. According to Cecelski, Hill was “a soft-spoken, spiritual man” who described the work of the Bellamy’s enslaved artisans as “unsurpassed.” Following are excerpts from the article, in William M. Hill’s words: My daddy was in building, and I’m guessing it was just in my blood. He didn’t finish the second grade, but he became a master plasterer. People beat a path to his door because he was good. He knew how to work. The appearance of his work was good. It was solid, it was sturdy. I learned everything from him. I stayed just as close to him as his underwear. I started with my daddy when I was 11 years old. My brother and I were there, there wasn’t anybody to keep us, so daddy carried us to the job. Plastering is as old as Time. It was done in biblical days. It was a means of covering up wood studs and wood ceiling joists, and it was done by hand, and still is. It hasn’t changed much. It takes four years to get from apprentice laborer to plasterer. But you never get above labor. You never get above that common job: making up that mortar, pushing a wheelbarrow, building a scaffold. You learn how to mix the mortar. Your plaster material is a rock, a mineral that comes out of the earth, and you mix it with sand and water. You learn how to put it on the wall or a ceiling with a trowel. It’s something that you learn the feel of with your hands. When I was 19 years old, he (Hill’s dad) turned the business over to me, lock, stock and barrel. In my younger years, I liked newer buildings: hit them and go. But I realized, in my older years, it is a challenge to go in something like the Bellamy Mansion, a building that is 150 years old. You have to get into the minds of those plasterers and they’re dead. If you don’t, you can’t redo what they’ve done.

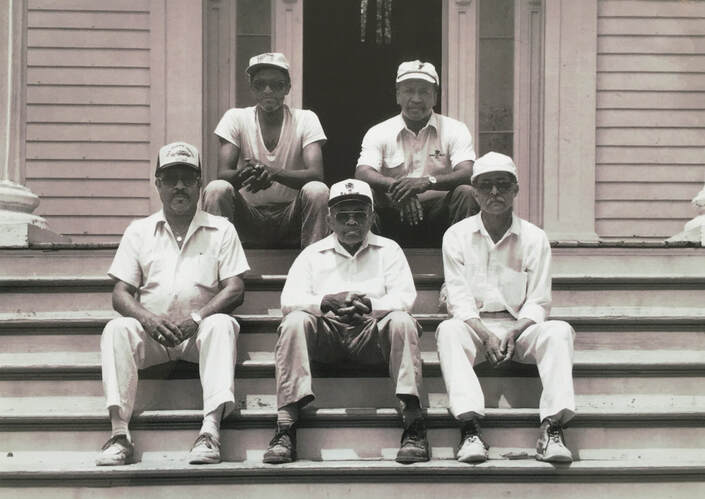

Now, to John Doe it might not mean a thing. But for me to go in there and take this stuff that is damaged by fire and time and restore it identical, that’s a challenge. He described his perfectionism to museum staff as standing in the center of the room, staring at the plaster, climbing up and down a ladder to retouch with a putty knife, for hours, inch by laborious inch, to get it right. A wood and metal template fabricated by the team, and used to get the curvature of crown molding, was one sign of Mr. Hill's aim to do this work in a similar manner to the original plasterers. William Hill (pictured below in 2008) worked on hospitals, city halls, courthouses, jails, schools, banks, theaters, and churches. His work can be found in buildings on the campuses of both UNC-Chapel Hill and NC State, and his plasterer's tool is forever immortalized in the Bellamy Museum northwest library. He died in 2022, aged 92.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Older Blog Posts

To see all previous blog posts, please click here. Blogs written after summer 2020 will be found on this page. AuthorOur blogs are written by college interns, staff, and Bellamy volunteers. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

|

Ticket Sales

10:00 am - 4:00 pm daily

Monday-Friday 9:30 am- 5 pm |

Admission Prices (tax not reflected)

Self-guided

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed