|

Following in the tradition of the original enslaved plasterers, William M. Hill, a second-generation master plasterer from Clinton, NC, and his team of artisans repaired extensive plaster damage resulting from the 1972 fire at the Bellamy Mansion. During 1992 and 1993 — 20 years after the blaze set by arsonists — they restored the ornamental plasterwork and fabricated the missing parts by hand. Hill's journey to become a master of his craft was a fascinating one, as uncovered by historian David Cecelski in a 2006 interview with Hill, then age 77, published in The Raleigh News & Observer. According to Cecelski, Hill was “a soft-spoken, spiritual man” who described the work of the Bellamy’s enslaved artisans as “unsurpassed.” Following are excerpts from the article, in William M. Hill’s words: My daddy was in building, and I’m guessing it was just in my blood. He didn’t finish the second grade, but he became a master plasterer. People beat a path to his door because he was good. He knew how to work. The appearance of his work was good. It was solid, it was sturdy. I learned everything from him. I stayed just as close to him as his underwear. I started with my daddy when I was 11 years old. My brother and I were there, there wasn’t anybody to keep us, so daddy carried us to the job. Plastering is as old as Time. It was done in biblical days. It was a means of covering up wood studs and wood ceiling joists, and it was done by hand, and still is. It hasn’t changed much. It takes four years to get from apprentice laborer to plasterer. But you never get above labor. You never get above that common job: making up that mortar, pushing a wheelbarrow, building a scaffold. You learn how to mix the mortar. Your plaster material is a rock, a mineral that comes out of the earth, and you mix it with sand and water. You learn how to put it on the wall or a ceiling with a trowel. It’s something that you learn the feel of with your hands. When I was 19 years old, he (Hill’s dad) turned the business over to me, lock, stock and barrel. In my younger years, I liked newer buildings: hit them and go. But I realized, in my older years, it is a challenge to go in something like the Bellamy Mansion, a building that is 150 years old. You have to get into the minds of those plasterers and they’re dead. If you don’t, you can’t redo what they’ve done.

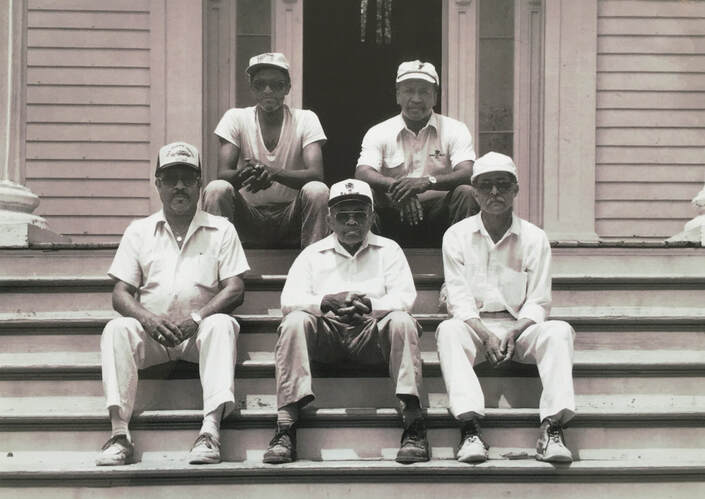

Now, to John Doe it might not mean a thing. But for me to go in there and take this stuff that is damaged by fire and time and restore it identical, that’s a challenge. He described his perfectionism to museum staff as standing in the center of the room, staring at the plaster, climbing up and down a ladder to retouch with a putty knife, for hours, inch by laborious inch, to get it right. A wood and metal template fabricated by the team, and used to get the curvature of crown molding, was one sign of Mr. Hill's aim to do this work in a similar manner to the original plasterers. William Hill (pictured below in 2008) worked on hospitals, city halls, courthouses, jails, schools, banks, theaters, and churches. His work can be found in buildings on the campuses of both UNC-Chapel Hill and NC State, and his plasterer's tool is forever immortalized in the Bellamy Museum northwest library. He died in 2022, aged 92.

0 Comments

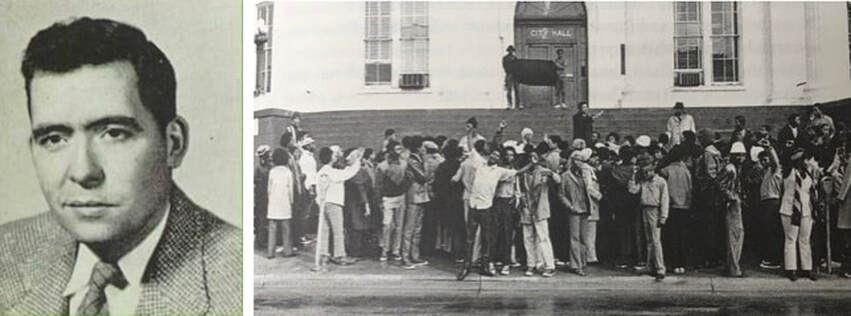

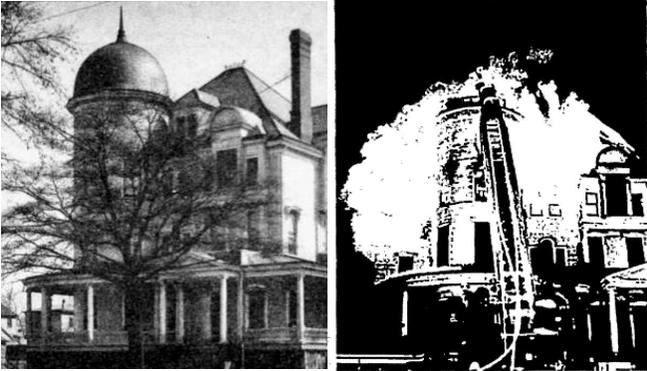

On March 13, 1972, disaster struck the Bellamy mansion. Arsonists poured gasoline on the floors and set fire to the house. Damage was most severe in the northwest room on the first floor and in the central passage. Plaster had fallen and broken in many rooms, wood was charred and some destroyed, and fixtures and mirrors were damaged. The antebellum house, built mostly by enslaved workers in 1861, and that had previously needed only ordinary repairs and repainting, now required major restoration. Still intact on the outside, the mansion stood fire-damaged and empty at the heart of the city of Wilmington. Although no culprits or motives were ever determined, the best theory behind the 1972 fire at the Bellamy Mansion is that it was political in nature. Throughout the south, public schools were being desegregated, bringing Black and White children together in the classrooms. New Hanover County, of which Wilmington is a part, had begun integrating its high schools in 1968. Black students were bused to the White schools and not given the same opportunities as the White students. It was a tumultuous time in Wilmington, scarred by protests, fires and widespread violence. In early February 1971, Black students staged a school boycott to protest systematic mistreatment by the city’s education authorities, teachers, police, and White adult thugs who harassed them on school grounds. Amid the chaos that ensued, a White-owned mom-and-pop store called Mike’s Grocery was burned. In March 1972, nine Black men (five of them high school students) and one White woman — the Wilmington Ten — were charged and convicted of that fire based on perjured testimony. How does the fire set by arsonists at the Bellamy Mansion factor into this narrative? Many observers at the time linked the arson to conflicts over the school district’s integration. Heyward C. Bellamy, a distant cousin of the family, was the Superintendent of Schools overseeing that effort, which was unpopular among both Whites and Blacks. He became a lightning rod for community tensions. Once, he was shouted down by angry Black students. On another evening, hundreds of sympathizers with the group Rights of White People demonstrated on Bellamy's lawn and let the air out of his car's tires. His name alone may have been the catalyst for the Bellamy fire. An alternate theory to the “fire of incendiary origin,” as described in the local newspaper, is that the Bellamy house may have been attacked as a symbol of the Old South. In early 1972, prior to the March fire, members of the Bellamy family formed a charitable corporation called Bellamy Mansion, Inc. to assure the preservation and restoration of the mansion and all its antebellum glory. For some Wilmingtonians, that may not have sat well. We simply don't know. Subsequent fires, for which the causes were unknown but were not ruled arson, destroyed the home of John D. Bellamy Jr. at 602 Market Street in August 1972, and the Robert Bellamy house in 1980 (the latter is now the parking lot for the Bellamy Museum). (Sources: Wilmington News article “Fire Hits Bellamy Mansion,” March 14, 1972; Catherine W. Bishir’s “The Bellamy Mansion”; Kenneth Robert Janken’s “The Wilmington Ten: Violence, Injustice, and the Rise of Black Politics in the 1970s”) |

Older Blog Posts

To see all previous blog posts, please click here. Blogs written after summer 2020 will be found on this page. AuthorOur blogs are written by college interns, staff, and Bellamy volunteers. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

|

Ticket Sales

10:00 am - 4:00 pm daily

Monday-Friday 9:30 am- 5 pm |

Admission Prices (tax not reflected)

Self-guided

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed