|

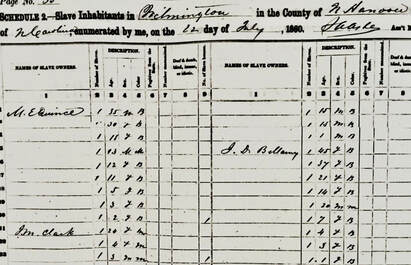

When his father died in 1826, nine-year-old John D. Bellamy inherited 21 enslaved people. By 1860 he owned 115 in North Carolina, spread across three counties. He had 82 enslaved men, women, and children working at "Grovely," Bellamy’s produce plantation in Brunswick County. In Columbus County, there were 24 enslaved men between the ages of 17-40 who lived and worked at "Grist," Bellamy’s turpentine plantation. And in New Hanover County at the 503 Market Street townhome, nine domestic enslaved workers maintained the property and served the Bellamy family and their guests. The museum is fortunate to know their names and something of their lives.

The Bellamys moved into the home with their eight children, who ranged in age from a 19-year-old daughter, Belle, to 18-month-old Chesley. Primary care of the youngest Bellamy children was the responsibility of Joan, an enslaved wet nurse and nanny. Joan’s young daughter, Caroline, was described in a family memoir as matriarch Eliza Bellamy’s “little maid” who followed her “foot to foot.” She likely helped Mrs. Bellamy with her morning routine while Joan roused and tended to the Bellamy children. As coachman, Guy cared for the carriage as well as the horses. Each morning he prepared to drive Dr. Bellamy to his properties, or take Mrs. Bellamy and the children to visit friends or relatives. He ran errands in town and needed written permission from the Bellamys to legally purchase goods. Laws regulated where and when enslaved people could go, with whom they could do business, and with whom they could spend their leisure time. Wilmington’s slave owners nevertheless often disregarded the laws if it benefitted them.  Similar to the image of an enslaved worker shown at left, Rosella spent most of her 16-hour workdays as a laundress. She washed and dried linens and clothing for the Bellamys and their guests in the slave quarters’ laundry room. She was likely assisted by Mary Ann; together they ironed in a basement room in the mansion. The youngest enslaved girls likely helped carry laundry bundles and fold napkins.  The slaves used these exterior stairs to move between the mansion’s floors as their daily work required. The enslaved women and girls who were not preoccupied with the Bellamy children, meal preparations, or laundry spent their afternoons climbing the slave stairs as they cleaned, dusted, polished silver, and readied the mansion for guests. Guy served the evening meal, while Caroline used a “shoo fly” to ensure diners’ meals were insect free. They would then tend to the needs of the family and their guests after dinner in the parlors while Sarah tidied the kitchen and Mary Ann washed dishes. Joan put the Bellamy children to bed, and after all guests left for the night, the slaves retired to their bed chambers. Their workday ended around 10 o’clock, but they were on-call 24 hours a day. After a few hours’ slumber, the market house bell rang and another day began.

Source: Bellamy Mansion Museum Slave Quarters Exhibit.

2 Comments

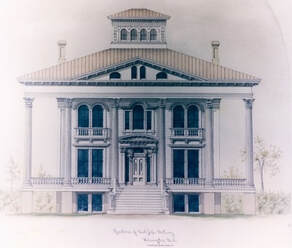

In February 1861, Dr. John D. Bellamy, his wife Eliza, and their eight children (with another on the way) moved into their new five-story home at 503 Market Street, Wilmington, NC. The Bellamy household was a large and labor-intensive one, with nine enslaved workers living on the site to attend to the family.

A complex water system allowed water captured from trough roof gutters to be pumped from a cistern under the back yard to supply running water within the house. The careful arrangement of doors and windows and vents brought cooling breezes from the shaded porch up through the house and out through the belvedere. Separate service zones and a back porch service staircase gave discreet access to the work yard, carriage house, and slave quarters at the rear. Although free Black and enslaved artisans built much of Wilmington’s architecture at the time, the Bellamy house was singled out by observers as having been constructed principally, if not entirely, by local Black workmen, including carpenters, masons, plasterers and interior finishers. Moreover, to a degree unusual in antebellum construction projects, the names of many of them have been identified. Among them were William Gould, Henry Taylor, George Price Sr. and Jr., Elvin Artis, Alfred and Anthony Howe, and members of the Sadgwar and Kellogg families.

|

Older Blog Posts

To see all previous blog posts, please click here. Blogs written after summer 2020 will be found on this page. AuthorOur blogs are written by college interns, staff, and Bellamy volunteers. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

|

Ticket Sales

10:00 am - 4:00 pm daily

Monday-Friday 9:30 am- 5 pm |

Admission Prices (tax not reflected)

Self-guided

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed