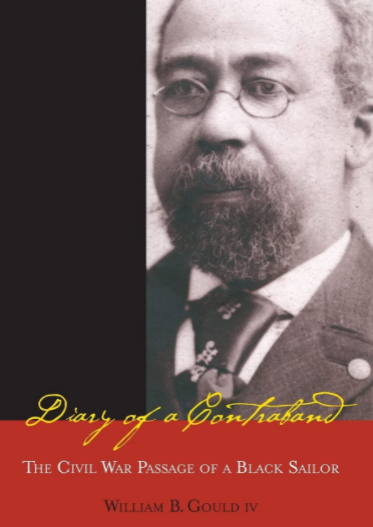

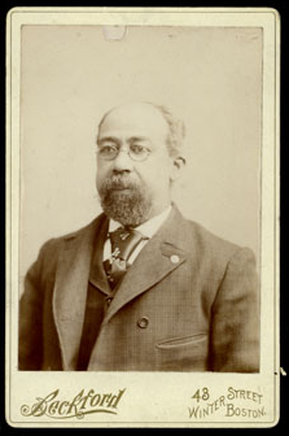

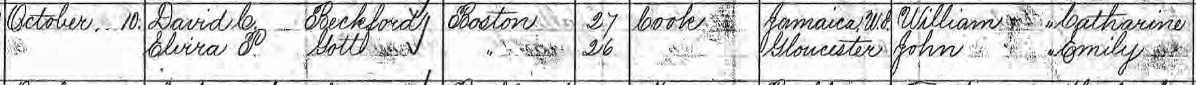

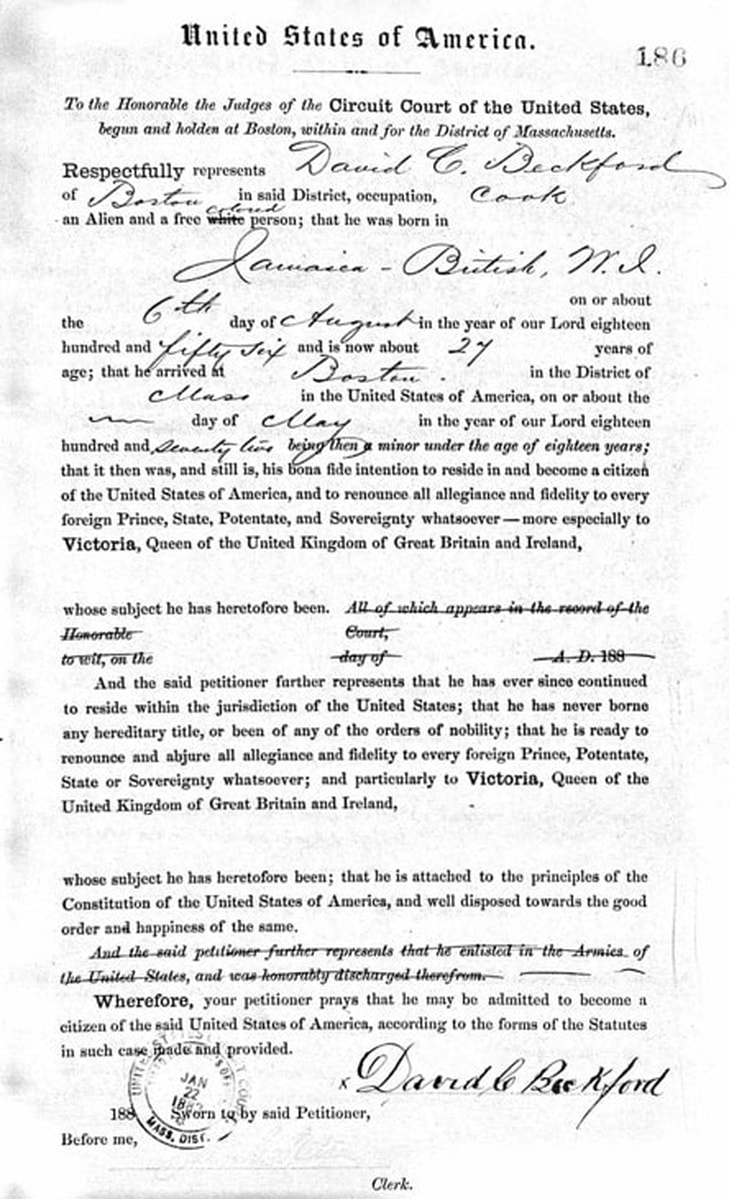

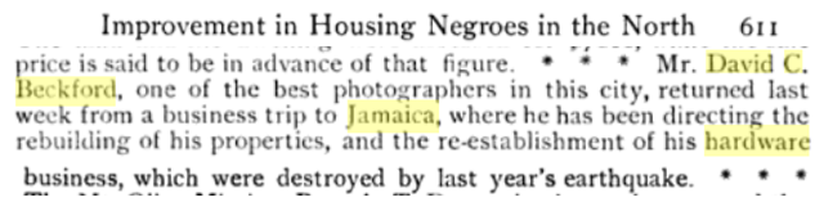

William B. Gould I was born into slavery but escaped to his freedom in 1862 where he went on to join the Union Navy and fought against the Confederacy for the remainder of the Civil War. Three days after his escape from Wilmington he began writing a diary that he would keep for the duration of his service, and his diary is the only one known to exist that was penned by a member of the Union Navy who was an escaped slave. Gould is one of the known antebellum artisans who helped with construction of the Bellamy house, and it may have been one of his last projects in the South as an enslaved plasterer. In 2002, William B. Gould's great-grandson, William B. Gould IV, published the diary, titled "Diary of a Contraband" because the escaped slaves taken aboard the Union blockading ship were considered missing contraband rather than missing people. On the cover of the book is a striking photograph of a bespectacled Gould with a greying goatee and a perfect Windsor knot in his silk tie.  The cover image is a closeup of a cabinet card taken at the Beckford photography studio in Boston, Massachusetts, and possibly the first photograph taken of Mr. Gould. This image of Mr. Gould is not the only one used at the Bellamy Museum in the interpretation of his story, but it is the one used most frequently. Staff and volunteers could recognize it from one thousand yards, but the year it was taken and the photographer who captured his stoic portrait had not come up as a topic of research. Over the last few years, Mr. Gould's story of enslavement, escape, enlistment, and entrepreneurship has begun to finally receive more regional and national recognition. Here in Wilmington, a state highway marker dedicated to Gould was installed in front of the Bellamy Museum in 2018. Plans to rename a park in Dedham, Massachusetts, the town Mr. Gould and his wife Cornelia settled in after the Civil War, came to fruition in September 2021 when the East Dedham Passive Park was renamed the William B. Gould Park, and his life story and obituary were featured in a "New York Times" article in June 2022. The grassroots organization responsible for much of this is the William Gould Memorial, and after years of planning and fundraising, the group just unveiled a life-size bronze statue of Mr. Gould situated in the park that now bears his name.  Bolivian-born artist Pablo Eduardo studied photographs of Gould to create the memorial, and though depicting an older man that the one in the Beckford photograph, many features from that photograph jump out when looking at the clay model on the left--from the hairline to that Windsor knot in the tie. The Beckford photograph of this brilliant man and stalwart patriot is, to us, iconic and central to telling Mr. Gould's story, but I had never stopped to ask myself, "Who was Beckford? When was the photograph taken? What, if anything, could knowledge of the photographer help illuminate about Gould himself?" What follows is a brief biography of David C. Beckford, a "colored" immigrant who went from working odd jobs when he arrived in the United States at age sixteen to one of the most renowned photographers in New England by the time he was in his mid-thirties. Ironically, no photograph of David C. Beckford is known to exist. David C. Beckford (c. 1855-unknown) was born in Jamaica, West Indies, to William and Catharine Beckford. David sailed to America in 1872 around the age of sixteen, and he worked various jobs including as a claerk and cook in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1881, at the age of twenty-seven, David married Elvira P. Gott of Gloucester, Massachusetts, and in 1882 David became a naturalized American citizen. Sometime after becoming an American citizen, David went to work for Boston based Chickering Photography Company--established in the early 1870s--and around 1891 David C. Beckford took over the studio and renamed it Beckford's Photo Studio. In a short time, Beckford's studio was renowned, and he employed four assistants. An 1892 publication, Boston: its Finance, Commerce, and Literature, called his studio "one of the best in the country" stating his portraits were "unsurpassed by any other house in New England." A client could have their photograph hand-colored with "crayon, pastel, water colors, India ink, and oil." A Directory of Massachusetts Photographers states Beckford's studio was in operation until 1909, and it may be at that point David C. Beckford moved back to Jamaica. Beckford was not only an entrepreneur in America, but he also maintained a hardware store in Kingston, Jamaica. He sailed back and forth between Boston and Kingston conducing business, and a 1905 passenger manifest from the ship Admiral Farragut lists David as the only "Colored" passenger aboard that voyage.  In 1907, the island of Jamaica suffered a 6.2 magitude earthquake--the epicenter of which was Kingston. It was one of the deadliest earthquakes in recorded history with around 1,000 people losing their lives. Every building in Kingston was damaged or destroyed including Beckford's hardware store and other properties. What became of David and Ella Beckford after 1909 is currently uknown. There are no death or burial records for either, and there is no evidence they had any children. It is plausible they moved back to Jamaica after the earthquake where they remained. David C. Beckford was a successful Black businessman in two countries. There were very few Black photographers in America when Beckford took the photograph of William B. Gould I around 1892-1895. It's quite a fascinating vignette to imagine this escaped slave turned Naval officer sitting for his portrait in a busy Boston studio operated by a young, up and coming Black immigrant. Written by Leslie Randle-Morton, Associate Director of the Bellamy Mansion Museum.

1 Comment

|

Older Blog Posts

To see all previous blog posts, please click here. Blogs written after summer 2020 will be found on this page. AuthorOur blogs are written by college interns, staff, and Bellamy volunteers. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

|

Ticket Sales

10:00 am - 4:00 pm daily

Monday-Friday 9:30 am- 5 pm |

Admission Prices (tax not reflected)

Self-guided

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed