Mirrors at the level of the gas fixtures were used, as were mirrors low to the ground. Sometimes they were built into furniture or into fireplace covers like the ones on display in the mansion. The covers, which were placed in front of the open fireplace any time it was not in use, were not used for women to check their ankle exposure, as an old wives' tale suggests, but to provide more light for everyone in the parlor. The entire Bellamy house was plumbed for gas when finished in 1861 and both wall-mounted and ceiling gas fixtures were placed in hallways and the nine bedrooms. The gasolier in the Bellamy's family parlor, shown below left, was made by Cornelius and Baker of Philadelphia. It is especially appealing with little cherubs blowing horns and decorative elements, including circus elephants. Given Dr. Bellamy's politics, it may be no coincidence that this gasolier is quite similar to the one also made by Cornelius and Baker in the White House of the Confederacy in Richmond, Va. (1861-1865). This gasolier is possibly one of seven attributed in 1896 to the original furnishings of the White House.

The Mirrors

Each mirrored fireplace cover in the Bellamy parlors has the maker’s mark “T. Bent & Son N.Y No. 18” on its back. Thomas Bent established the Globe Iron Foundry in 1843 in New York, NY. The company was well known for their stable and kennel fixtures and fittings. In 1860 Dr. and Mrs. Bellamy may have visited the Globe Iron Foundry at their 26th Street Manhattan shop to purchase not only the fireplace covers but also stable fittings for the carriage house and possibly decorative iron benches for outside. Thomas Bent died in 1870 and his son Samuel took over the company. By 1890 Samuel had moved the foundry from New York City to Port Chester where it became Samuel S. Bent & Son. (Source: The Iron Age, Vol. 46, September 1890.)

0 Comments

A lonely, dirty, dangerous business: Extracting this 'pine tar' is described by historian David Cecelski; "A 'boxed tree' was one that had a section of its bark cut away so that the resin flowed into the hollow in the tree where it could be collected. To make 'spirits of turpentine,' the woodsmen and women (often enslaved laborers) collected and distilled that resin, not terribly unlike making liquor." [2] Given that pine resin featured in so many products, plus preserved wood and waterproofed ships, it was unsurprising that North Carolina, one of the world's leading sources, accumulated so much wealth from its pine trees. As lucrative as it was for the White land owners, the industry could be solitary and physically taxing for the enslaved workers. The industry used the task system. An overseer assigned enslaved workers a task, or multiple tasks, and they were responsible for completing them. This meant an enslaved naval stores worker could continue with limited or no supervision for several days at a stretch. Shoes, hats and blankets were often the only items enslaved workers on these turpentine farms had that were not made on site. Different from plantation life, where families were often housed together, laboring in a turpentine operation could be more solitary with perhaps only a small number of female enslaved cooks with the male laborers. Working conditions were harsh. Summer heat, mosquitoes, poisonous snakes and poison ivy, among much else, were prevalent and led to a variety of maladies. Wet ground and forests made it difficult if not impossible to move carts led by mules.

When enslaved people would stir pine tar, pitch and turpentine, it was often in huge cauldrons that required them to stand on the edge and use a long stirrer, almost like an oar. One slip could lead to severe burning. In this case, being a “Tar Heel” was certainly not a good thing. In 1850 there were 1,144 distillers of pine tar products in the state, and most had businesses in Wilmington. By 1860 the value of this trade was over $5 million. [5] To that point, an unproven story, likely an apocryphal boast but certainly indicative, relayed by John Bellamy Jr. in his manuscript, Memoirs of an Octogenarian (readable here), was that one year's profit from one of his father's plantations paid for the Bellamy house in Wilmington. As with cotton and rice plantations on the Cape Fear the hard work of enslaved Black workers was central to this egregiously unequal economy and society.

[1] William S. Powell (March 1982). "What's in a Name? Why We're All Called Tar Heels". Tar Heel magazine

[2] David Cecelski (reviewing 1809 diary excerpts from English traveler Holles Bull Way), Coastal Review article, July 2018, coastalreview.org.https://coastalreview.org/2018/07/pitch-pines-and-tar-burners-a-1792-account/ [3] Dr. Lloyd Johnson. https://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/naval-stores/ [4] David Cecelski (reviewing 1809 diary excerpts from English traveler Holles Bull Way), Coastal Review article, July 2018, coastalreview.org.https://coastalreview.org/2018/07/pitch-pines-and-tar-burners-a-1792-account/ [5] Dr. Lloyd Johnson. https://northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/naval-stores/ [6] Article, WUFT Public Media, Veronica Nocera. May 9, 2024. www.tuft.org/environment/2024-05-09/the-trees-truth-once-dominant-longleaf-pines-face-the-growing-threat-of-climate-change

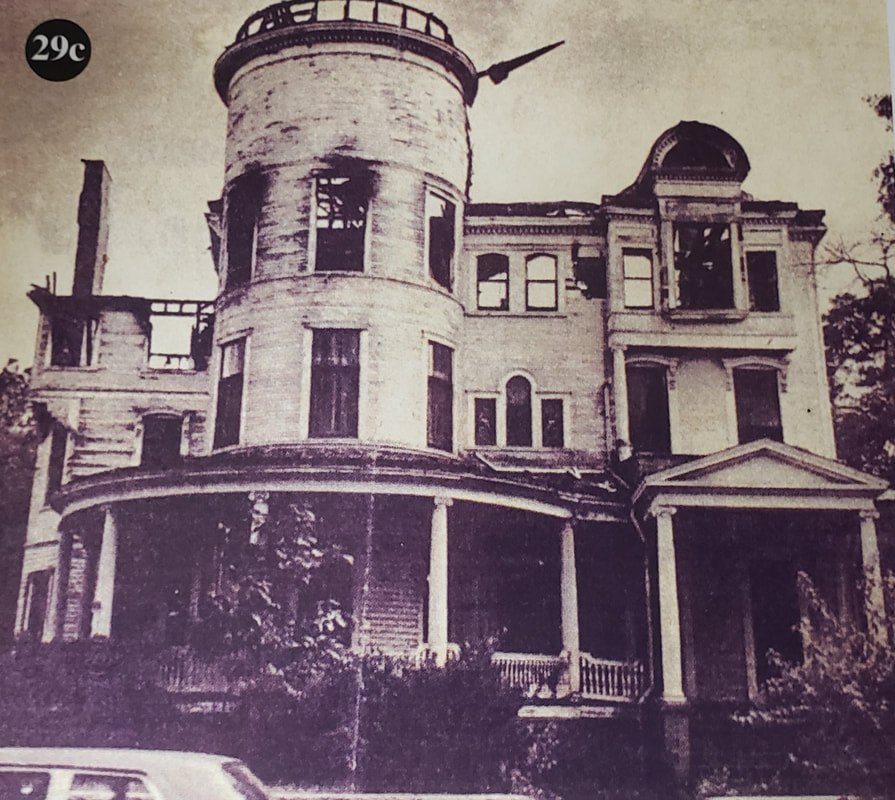

The unrestored mansion as it looked when Don spotted it during a trip to Wilmington. The unrestored mansion as it looked when Don spotted it during a trip to Wilmington. Don’s fascination with the Bellamy Mansion began in 1968, Sharpe observed, when he traveled to Wilmington for the Azalea Festival air show. As he rode past the mansion it captured his imagination. At that time there was a store, Divine Antiques, run by Virginia Jennewein, in the basement. The rest of the home was unoccupied. He stopped to look in but was refused permission to see the rest of the interior. In response, he made the rash statement that he would etch and donate the glass for the front door should it be restored. The woman in the antique store replied, “Anybody that damned crazy can go in.” A few years after that, Sharpe remembers visiting Floyd Hardware and found Don in a state of alarm. "He was grieving that the Bellamy mansion in Wilmington had been the victim of arsonists. The fire in the mansion which occurred during the early ‘70s came at a time of racial troubles, and Don deeply feels the irony of this because the house is an example of the genius of Black artistic craftsmanship, one of the finest Greek revival buildings in the entire South.”

More recently, Don took on the task of reproducing skeleton keys for the four adult bedroom level closets. The term ‘skeleton key’ refers to any key that can open multiple locks. Incidentally, closets were present in Europe from the 1500s but were usually whole rooms. America refined the idea into reach-in closets within walls in the mid 1800s. Early clothes closets employed pegs, although Thomas Jefferson reputedly had a hanger device in Monticello. One fine story of invention is that in 1903, Albert J. Parkhouse of the Timberlake Wire and Novelty Company in Jackson Mississippi, couldn't find a spot to hang his coat and upgraded the clothes peg idea by twisting wire into the shape we recognize as the modern hanger. Whatever the truth of these details, the Bellamy's locking closets, like the gasoliers and fixtures Don also fixed, were part of the ever-evolving world of domestic living.

The original mirror frames were finished with gold leaf. During the 1970s and 80s, while restoring the frames in his home workshop, the gilt would catch Don's eye and take his thoughts back to those original glory days of the house. He added that thinking of that Civil War era also called to mind the quote from Winston Churchill that, “History is written by the victors.” While considering the thousands of lives that were lost on both sides, Don laments there are no victors in war. In his view, both Confederates and Yankees came away physically and mentally crippled. Taking on an historic preservation project, which takes much time and attention to detail, often leads to reflection on the lives of those who came before.  Another tricky project was the restoration of the molding above the gasoliers. The parlor gasoliers were lit with coal gas, a by-product of naval stores processing. The medallions above the gasoliers were decorative, but served a practical purpose in hiding soot from the coal gas. The original medallions above the front parlor gasolier were, Don notes, "shaken loose by a group of kids on a tour in the house jumping up and down on the floor of the room above.” They had to be cleaned up and, in some cases, recast in plaster. Don shared some memories about restoring these and the similarly involved crown molding in the foyer. Doing the work at home, it attracted the attention of some neighborhood kids who asked if they could help. He let them pour some of the molding material and before it dried, he invited the kids to put their names on the backs of the molds. That idea came from the discovery, during Preservation NC's 1990s restoration, of the 'WBG' initials on the back of an original piece of plaster in the house. The story of it's discovery and the man who inscribed it is a mainstay of museum tours today. WBG was William Benjamin Gould, an enslaved plasterer who worked on many antebellum homes in the Wilmington area, including Bellamy's, and made a daring escape downriver in 1862. Letting the kids etch their names was a nod to this fascinating history and Gould, the skilled enslaved craftsman who had originally created this beautiful plasterwork in 1860.

Check out some pictures of the mansion and slave quarters restoration. Our website features a before and after gallery here. There you can appreciate Don's decades of work, as well as that of many other preservation experts.

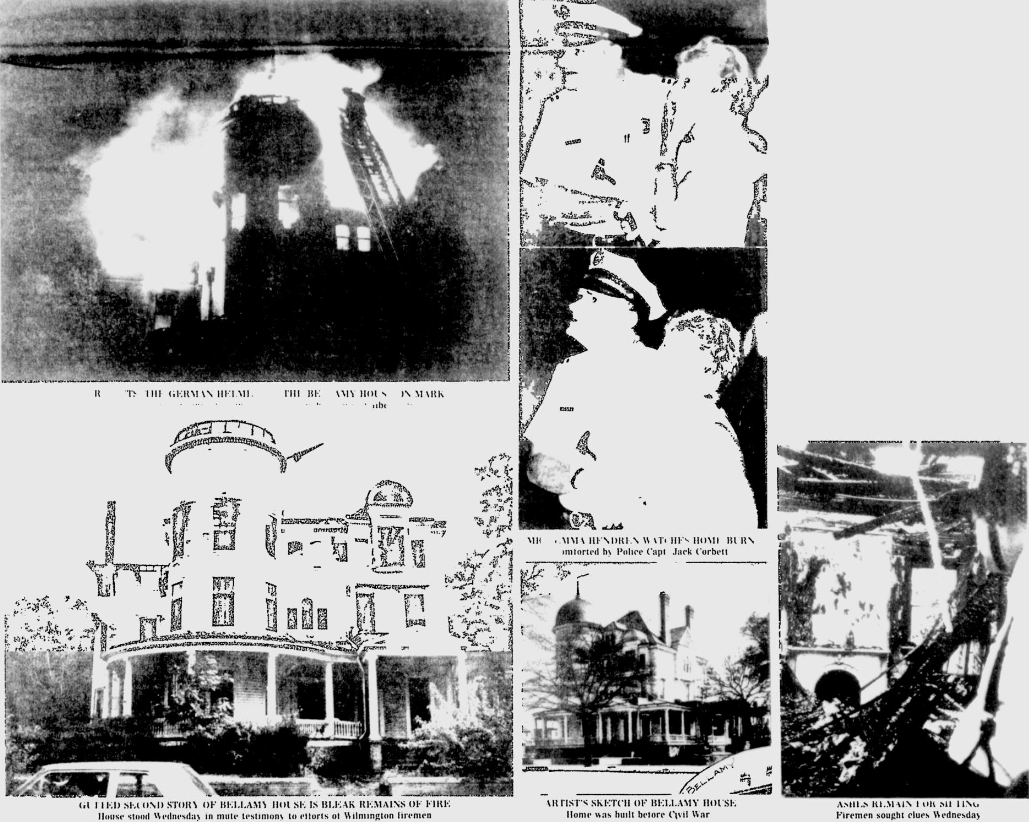

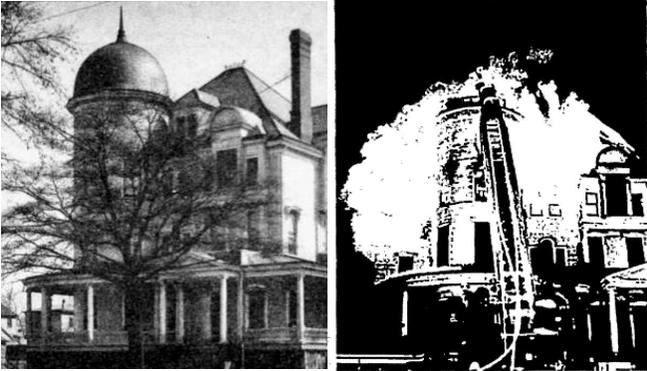

The Robert R. Bellamy House. Of Eliza and John Bellamy's 10 children, Robert Rankin Bellamy (1861-1926) was the only one born in what is now the main house of the Bellamy museum at 503 Market St. He grew up in the house and became a successful drug store owner and pharmacist in downtown Wilmington. Robert had his own Queen Anne style home built next door to the original Bellamy mansion around 1895. Robert married Lilly Dale Hargrove (1862-1934) and they had one child, Hargrove Bellamy (1896-1994) in the house at 509 Market St. The picture below is approximately 1905. As you can see, it was a large and imposing structure. The Rachel Thompson house (513 Market St., far right in the historic image above and painted yellow in the present day image below) was bought by Robert Bellamy in 1890 as a rental property. He enlarged that house over time. Robert's house burned on Christmas Day in 1980 while in use as a home for children with disabilities, according to the local paper. At that time the building was known locally as the Tabb mansion. The building was lost but no-one was hurt. The John D. Bellamy Jr. House. One block away from the current museum site, at 602 Market St., sat the John D. Bellamy Jr. house. John Jr. (1854-1942) grew up in what is now the museum's main house. He was an attorney and politician whose election to the US House of Representatives was an integral part of the 1898 massacre and coup. Bellamy had acquired an imposing Italianate, James F. Post designed, 1858 house (Wright-Harriss-Bellamy) on the south east corner of 6th and Market sts. in the 1890s. Around 1899 he massively remodeled it in an extravagant, late Victorian, Queen Anne style. A tower, referred to locally as the ‘German helmet’, and decorative porches were added. The renovation, by noted local architect Charles McMillen, was equally grand on the inside. The local newspaper marveled at the elaborate oak, cherry, and mahogany interior woodwork, a ball room that was created on the top floor, and paneled silk, onyx fireplaces and tapestries by decorators Duryea and Potter of New York.  A circa 1901 image shows the enormous changes to the house. As well as the tower, chimneys, porches, roof, gables and many other features that were rebuilt, there was interior paneling, wainscoting, ceiling beams, and mosaic tiles in both the vestibule and new conservatory. Walls and ceilings were either painted with floral designs or covered with paneled silks or tapestries. On Monday, March 13 ,1972 the original Bellamy mansion, now the museum, suffered an arson attack. While there was no evidence of arson, John Jr.'s house burned down on Wednesday, August 23rd, 1972. John Bellamy Jr's grand-daughter, Emma Bellamy Williamson Hendren (1902-1992) lived in the house at the time. Again, fortunately, no-one was injured.  1972 image from New Hanover County Public Library by way of Beverly Tetterton's book, Wilmington: Lost But Not Forgotten. The Wilmington Morning Star for August 24, 1972 reported, "The German helmet is gone now. It was among the first sections of the house to fall. The 'spike' atop the 'helmet' toppled down into the body of the building." Credits for information and images to Beverly Tetterton, Wilmington Lost But Not Forgotten (2005), Susan Taylor Block, Cape Fear Lost (1999), New Hanover County Library North Carolina Room collections, the Wilmington Star-News archives, and the Bellamy Museum archives.

Since 2015, the Bellamy Mansion Museum has conducted free, place-based school tours in February and March for New Hanover County 5th graders. Staff and volunteers showed students both the 1859 slave quarters and 1861 main house to describe how life looked before electricity, or even running water. "As the 5th grade curriculum changed, tour attendance dropped, so we decided to revisit the program," explains Jen Fenninger, Education & Engagement Director. "In collaborating with New Hanover County Schools, [headquartered in Wilmington, NC], museum staff learned that the 1898 Wilmington Massacre and Coup has become of increased emphasis in the 8th grade social studies curriculum. With that in mind, recalibrating the tour to target 8th graders became a major initiative in the last year." With financial support from Bellamy Mansion Museum board members, local 8th grade teachers were invited to the museum and offered a paid day of professional development. The conversation focused primarily on the enslaved individuals who had lived on the site and extended to the 1898 massacre and coup. The Bellamy site lends itself directly to the teaching of these local history topics. During the development session, teachers were offered a 90 minute tour, an 1898 presentation, resource guide materials, and museum staff perspectives on how to teach topics of historical slavery and race through the site. "We had a great discussion and gained information about the topics to target and they how they can be paralleled with the curriculum content," Jen says. "In subsequent months, we rewrote our script to be appropriate and useful to the 8th grade classes." Through this process, Jen notes, "we were also able to increase our collaboration with colleagues at the nearby Cape Fear Museum (CFM). CFM has an 1898 field trip at a similar time of year that includes a mapping activity and timeline of events. The Bellamy site and CFM's artifacts and documentation blend well into a more complete picture of this period of history and the themes that arise. The new partnership has widened our reach within the county. From our day with local teachers, we learned that it is difficult for them to complete a field trip that isn't a full day out of their school building. Now, with students attending both museum locations, they experience a fuller, more versatile field trip, and learn in buildings where enslaved people once lived and worked." --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- " I cannot say thank you enough to everyone who played a part in the field trip! It was so well organized and put together. The adults and students really had a great time! I spoke to many of the students, and most of them said it was a 9 out of 10. Overall, the experience was incredible!" Trask Middle School teacher ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bellamy staff is supporting further efforts to educate teachers not only locally, but across the state by participating in symposiums held by the North Carolina History Center on the Civil War, Emancipation & Reconstruction out of Fayetteville, NC. With instruction coming from local historians, including Leslie Randle-Morton, associate director of the Bellamy Museum, the center held a two-day symposium last month in Wilmington. The purpose of the symposium is to teach historical perspectives on the war - its central point being that it was fought to preserve the system of enslavement. The Center reinforces this proven fact and ensures today’s school children learn the truth about the motivations behind the Civil War. The overall mission of the NC History Center on the Civil War, Emancipation & Reconstruction is to tell the stories of all North Carolinians and create a comprehensive, fact-based portrait of history that spans the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction periods. The Center is planning to hold a total of 12 symposiums as a lead up to the opening of a state historic site at the Fayetteville Arsenal where U.S. General William Tecumseh Sherman destroyed the Confederate Army’s ability to make weapons. Once the center is complete, which is expected in 2027, it will be turned over to the state and be housed within the museums division of the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

Bellamy family members had formed a charitable corporation in 1972 named Bellamy Mansion, Inc. to assure the preservation and restoration of the site. However, that year arson in the main house caused this undertaking to be vastly more costly and complex than anyone could have anticipated. Meanwhile, PNC was oriented toward finding private buyers who would restore needy properties into homes or adaptive uses such as offices or B&B’s. They were not really in the business of museums, but the Bellamy site offered a unique challenge and opportunity. The site was completed in 1861 and in 1946 the last member of the original family, Ellen Bellamy, passed away in the house. The property was in some disrepair, although it still comprised the house, gardens, former slave quarters and the carriage house. The latter was in such poor shape that it was bulldozed by the City just after Ellen died.

PNC spent four years working with the board of Bellamy Mansion, Inc. to help raise funds for site restoration. The plan was to restore the main house and then the whole site. PNC was committed to doing a “museum in the house” rather than a traditional house museum. This meant not completely furnishing the site but instead leaving room for exhibits, special events and programming. The idea became a hybrid that allowed for both a community hub and place-based learning. April 1994 marked the official opening of the site as the Bellamy Mansion Museum of History and Design Arts. Festivities kicked off on April 9 with a gala opening, a black tie fundraising event at the museum drawing more than 250 guests from Wilmington, the state and around the country. Music from the USMC 2nd Division Band in their dress blues filled the house. Over $25,000 was raised from the event to help pay for restoration work.

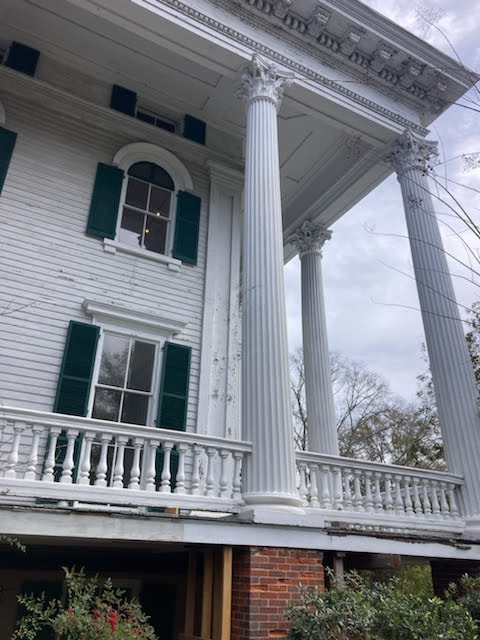

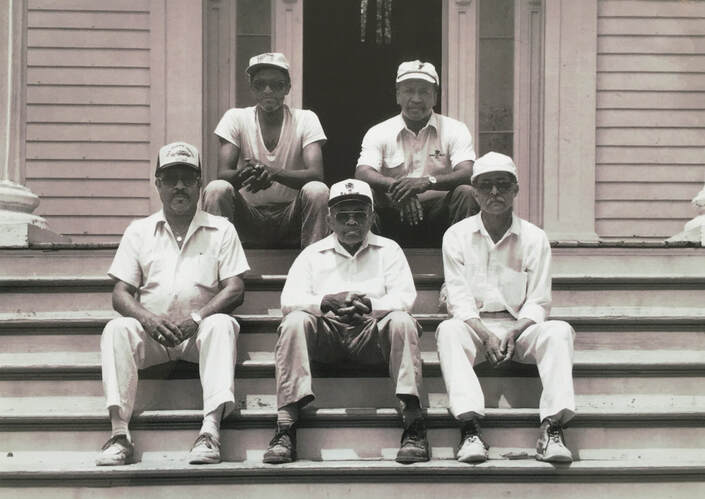

The next day, a Sunday, the general public was invited to join in the Grand Opening Celebration and ribbon-cutting. Playing a key role in the planning, volunteers had worked for eight months to get the museum open to the public. Lillian Boney, a founding member of the Board and great granddaughter of John D. Bellamy, cut the ribbon symbolizing completion of the interior restoration. Source: StarNews, July 2019, "Myrick Howard 'Birthday Bash' will observe Bellamy Mansion Museum's 25th year"; Catherine Bishir's The Bellamy Mansion. In the late 1930s Ellen Douglas Bellamy, the last member of the original family to live in the mansion, completed her memoir, Back With The Tide. In it, she mentions her sister, Mary Elizabeth, as having admired the Clarkson house in Columbia, SC while in college. Mary Elizabeth had reportedly sketched it to send to their father as a suggestion for a design type he might use for their new family home at 5th and Market sts. in Wilmington. The sketch is lost to time and the Clarkson house was burned by Gen. Sherman's army in 1865. However, we might imagine it had some of the Greek Revival style features that - along with Italianate elements - were drawn by architects James Post and Rufus Bunnell for John Bellamy. The house, slave quarters, and carriage house were built by enslaved and free Black artisans. Their skill is evident in the longevity and high style of the site. The buildings are the artifacts of the site and their preservation honors the stories of all those who built them.  The architectural features include the fourteen Corinthian columns on the house porches. In 2022, during a painting project, we discovered a good deal of rotten wood on one near the west corner of the house. All the columns are original and approximately 26 feet tall, including bases and capitals. They are cypress, a wood that is both water and termite resistant. The damage was to a bottom section that seems to have been patched many years ago. Water may have intruded through nail holes and failing paint over time. Some of those nails were the original handmade ones. The columns stand on square concrete plinths that don't allow drainage if water gets inside. Water can wick back up the wood and cause damage. These columns were shipped from New York during the house's construction in 1860-61. They are in sections, essentially three hollow cylinders stacked on top of each other. The tapering of the column narrows as it rises and features entasis - a classical term for a curved surface that adds aesthetics and strength to structural elements. Despite being essentially hollow they are load-bearing for some of the weight of the porch roof. The rotting lower third and base (pictured below) of this particular column was supporting very little weight and clearly needed replacement. We had braced it and, as we're a preservation organization, the idea was to salvage as much as possible and rebuild using similar materials and techniques. Jason Moore, a carpenter and owner of Trimight LLC, is known locally for meticulous work on historic detail of this kind. E.B. Pannkuk at Stature Engineering created drawings of the construction and Jason took extremely careful measurements of all parts of the column. Each column is slightly different due to them being made with hand tools and machinery over 160 years ago. Any repairs would have to be similarly custom. A good deal of geometry and math is needed as the bottom third has to correspond exactly with the section above when they meet. The joint is not a straight line but a series of interlocking cypress boards. The column is actually twelve boards at the bottom section that have beveled edges which can be placed together to create the cylindrical shape. Between a number of these boards are tiny shims - wafer thin pieces of wood that allow for expansion and contraction. There are also four wooden disks inside the column to which the boards are nailed to form the cylinder. These disks are at the base, at seven feet, then sixteen feet, and at the capital. Due to tapering the circumference of the column shaft is 26 inches at the base and 24 at the top. While initially the replacement boards could be machined, all the refinement to get them to fit exactly were pared with hand planes and chisels, plus careful sanding. The exterior of the column is an overlay of fluted, hand-shaped cypress wood. That fluted veneer is tacked to the underlying boards and also has to be recreated by hand. Each indent of that fluting is fractionally different as they were handmade to fit the board underneath. The base, which had also all but rotted away, has a maximum circumference of thirty-one inches but is actually three differently-sized, ornamentally curved, rings placed on top of each other. It almost goes without saying that those had to be very carefully hand finished as well. Sealant and oil-based primer finished the job after several months of detailed work. Over four hundred hours went into this project from start to finish. A benefit of our new knowledge and templates is that as other issues come up, we know what to do. For this particular column, we hope to get at least another century out of it. Huge thanks are due to a slew of supporters who helped us with very generous gifts from 2021 onwards as we figured out what was going on and how to properly fix it. Also our gratitude to the Cannon Foundation of Concord, NC for a preservation grant that spurred the work forward at a critical moment. Historic preservation work is a collective effort. The last word goes to Jason Moore, who notes he tried to use original methods, "so as not to limit the imagination of those that view the house after us. Getting to know Bellamy has been a humbling experience. The integrity of what has been built before can only be honored by putting forth a similar effort of excellence. Every house has a soul, Bellamy’s soul is awe inspiring." Following in the tradition of the original enslaved plasterers, William M. Hill, a second-generation master plasterer from Clinton, NC, and his team of artisans repaired extensive plaster damage resulting from the 1972 fire at the Bellamy Mansion. During 1992 and 1993 — 20 years after the blaze set by arsonists — they restored the ornamental plasterwork and fabricated the missing parts by hand. Hill's journey to become a master of his craft was a fascinating one, as uncovered by historian David Cecelski in a 2006 interview with Hill, then age 77, published in The Raleigh News & Observer. According to Cecelski, Hill was “a soft-spoken, spiritual man” who described the work of the Bellamy’s enslaved artisans as “unsurpassed.” Following are excerpts from the article, in William M. Hill’s words: My daddy was in building, and I’m guessing it was just in my blood. He didn’t finish the second grade, but he became a master plasterer. People beat a path to his door because he was good. He knew how to work. The appearance of his work was good. It was solid, it was sturdy. I learned everything from him. I stayed just as close to him as his underwear. I started with my daddy when I was 11 years old. My brother and I were there, there wasn’t anybody to keep us, so daddy carried us to the job. Plastering is as old as Time. It was done in biblical days. It was a means of covering up wood studs and wood ceiling joists, and it was done by hand, and still is. It hasn’t changed much. It takes four years to get from apprentice laborer to plasterer. But you never get above labor. You never get above that common job: making up that mortar, pushing a wheelbarrow, building a scaffold. You learn how to mix the mortar. Your plaster material is a rock, a mineral that comes out of the earth, and you mix it with sand and water. You learn how to put it on the wall or a ceiling with a trowel. It’s something that you learn the feel of with your hands. When I was 19 years old, he (Hill’s dad) turned the business over to me, lock, stock and barrel. In my younger years, I liked newer buildings: hit them and go. But I realized, in my older years, it is a challenge to go in something like the Bellamy Mansion, a building that is 150 years old. You have to get into the minds of those plasterers and they’re dead. If you don’t, you can’t redo what they’ve done.

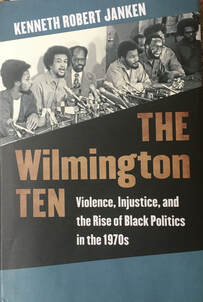

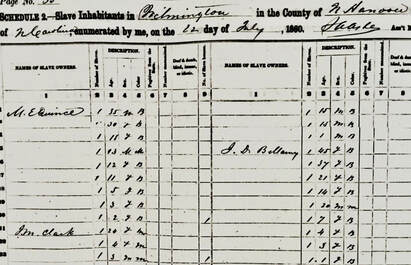

Now, to John Doe it might not mean a thing. But for me to go in there and take this stuff that is damaged by fire and time and restore it identical, that’s a challenge. He described his perfectionism to museum staff as standing in the center of the room, staring at the plaster, climbing up and down a ladder to retouch with a putty knife, for hours, inch by laborious inch, to get it right. A wood and metal template fabricated by the team, and used to get the curvature of crown molding, was one sign of Mr. Hill's aim to do this work in a similar manner to the original plasterers. William Hill (pictured below in 2008) worked on hospitals, city halls, courthouses, jails, schools, banks, theaters, and churches. His work can be found in buildings on the campuses of both UNC-Chapel Hill and NC State, and his plasterer's tool is forever immortalized in the Bellamy Museum northwest library. He died in 2022, aged 92. On March 13, 1972, disaster struck the Bellamy mansion. Arsonists poured gasoline on the floors and set fire to the house. Damage was most severe in the northwest room on the first floor and in the central passage. Plaster had fallen and broken in many rooms, wood was charred and some destroyed, and fixtures and mirrors were damaged. The antebellum house, built mostly by enslaved workers in 1861, and that had previously needed only ordinary repairs and repainting, now required major restoration. Still intact on the outside, the mansion stood fire-damaged and empty at the heart of the city of Wilmington. Although no culprits or motives were ever determined, the best theory behind the 1972 fire at the Bellamy Mansion is that it was political in nature. Throughout the south, public schools were being desegregated, bringing Black and White children together in the classrooms. New Hanover County, of which Wilmington is a part, had begun integrating its high schools in 1968. Black students were bused to the White schools and not given the same opportunities as the White students. It was a tumultuous time in Wilmington, scarred by protests, fires and widespread violence. In early February 1971, Black students staged a school boycott to protest systematic mistreatment by the city’s education authorities, teachers, police, and White adult thugs who harassed them on school grounds. Amid the chaos that ensued, a White-owned mom-and-pop store called Mike’s Grocery was burned. In March 1972, nine Black men (five of them high school students) and one White woman — the Wilmington Ten — were charged and convicted of that fire based on perjured testimony. How does the fire set by arsonists at the Bellamy Mansion factor into this narrative? Many observers at the time linked the arson to conflicts over the school district’s integration. Heyward C. Bellamy, a distant cousin of the family, was the Superintendent of Schools overseeing that effort, which was unpopular among both Whites and Blacks. He became a lightning rod for community tensions. Once, he was shouted down by angry Black students. On another evening, hundreds of sympathizers with the group Rights of White People demonstrated on Bellamy's lawn and let the air out of his car's tires. His name alone may have been the catalyst for the Bellamy fire. An alternate theory to the “fire of incendiary origin,” as described in the local newspaper, is that the Bellamy house may have been attacked as a symbol of the Old South. In early 1972, prior to the March fire, members of the Bellamy family formed a charitable corporation called Bellamy Mansion, Inc. to assure the preservation and restoration of the mansion and all its antebellum glory. For some Wilmingtonians, that may not have sat well. We simply don't know. Subsequent fires, for which the causes were unknown but were not ruled arson, destroyed the home of John D. Bellamy Jr. at 602 Market Street in August 1972, and the Robert Bellamy house in 1980 (the latter is now the parking lot for the Bellamy Museum). (Sources: Wilmington News article “Fire Hits Bellamy Mansion,” March 14, 1972; Catherine W. Bishir’s “The Bellamy Mansion”; Kenneth Robert Janken’s “The Wilmington Ten: Violence, Injustice, and the Rise of Black Politics in the 1970s”) When his father died in 1826, nine-year-old John D. Bellamy inherited 21 enslaved people. By 1860 he owned 115 in North Carolina, spread across three counties. He had 82 enslaved men, women, and children working at "Grovely," Bellamy’s produce plantation in Brunswick County. In Columbus County, there were 24 enslaved men between the ages of 17-40 who lived and worked at "Grist," Bellamy’s turpentine plantation. And in New Hanover County at the 503 Market Street townhome, nine domestic enslaved workers maintained the property and served the Bellamy family and their guests. The museum is fortunate to know their names and something of their lives.

The Bellamys moved into the home with their eight children, who ranged in age from a 19-year-old daughter, Belle, to 18-month-old Chesley. Primary care of the youngest Bellamy children was the responsibility of Joan, an enslaved wet nurse and nanny. Joan’s young daughter, Caroline, was described in a family memoir as matriarch Eliza Bellamy’s “little maid” who followed her “foot to foot.” She likely helped Mrs. Bellamy with her morning routine while Joan roused and tended to the Bellamy children. As coachman, Guy cared for the carriage as well as the horses. Each morning he prepared to drive Dr. Bellamy to his properties, or take Mrs. Bellamy and the children to visit friends or relatives. He ran errands in town and needed written permission from the Bellamys to legally purchase goods. Laws regulated where and when enslaved people could go, with whom they could do business, and with whom they could spend their leisure time. Wilmington’s slave owners nevertheless often disregarded the laws if it benefitted them.  Similar to the image of an enslaved worker shown at left, Rosella spent most of her 16-hour workdays as a laundress. She washed and dried linens and clothing for the Bellamys and their guests in the slave quarters’ laundry room. She was likely assisted by Mary Ann; together they ironed in a basement room in the mansion. The youngest enslaved girls likely helped carry laundry bundles and fold napkins.  The slaves used these exterior stairs to move between the mansion’s floors as their daily work required. The enslaved women and girls who were not preoccupied with the Bellamy children, meal preparations, or laundry spent their afternoons climbing the slave stairs as they cleaned, dusted, polished silver, and readied the mansion for guests. Guy served the evening meal, while Caroline used a “shoo fly” to ensure diners’ meals were insect free. They would then tend to the needs of the family and their guests after dinner in the parlors while Sarah tidied the kitchen and Mary Ann washed dishes. Joan put the Bellamy children to bed, and after all guests left for the night, the slaves retired to their bed chambers. Their workday ended around 10 o’clock, but they were on-call 24 hours a day. After a few hours’ slumber, the market house bell rang and another day began.

Source: Bellamy Mansion Museum Slave Quarters Exhibit. |

Older Blog Posts

To see all previous blog posts, please click here. Blogs written after summer 2020 will be found on this page. AuthorOur blogs are written by college interns, staff, and Bellamy volunteers. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

|

Ticket Sales

10:00 am - 4:00 pm daily

Monday-Friday 9:30 am- 5 pm |

Admission Prices (tax not reflected)

Self-guided

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed